Every Bug You Catch Is a Bug You Let Exist

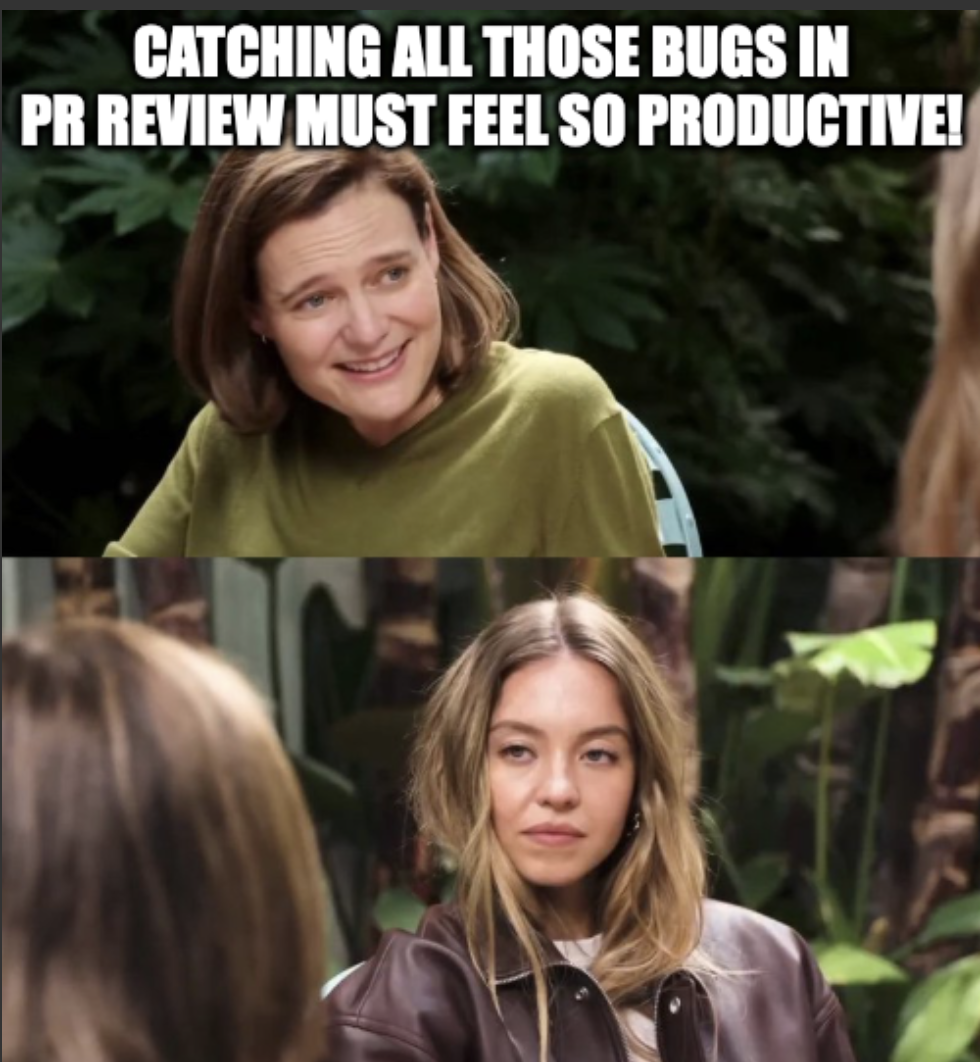

TL;DR: Catching bugs feels productive. That's the trap.

Every bug you catch in PR review is a bug you let exist long enough to need catching.

You didn't prevent it. You intercepted it. Late. After your agent wrote it, committed it, pushed it, opened a PR, waited for your attention, and finally—finally—you noticed.

That's a lot of ceremony for "you used the wrong import."

I learned this lesson twice. The first time was in a warehouse.

Louisville, Kentucky. Holiday peak, 2012. I was running inbound exception handling at an Amazon fulfillment center. New conveyor hardware was creating chaos—packages getting stuck, mis-sorted, lost in the system.

I'd built a system to manage it. Color-coded dashboards. Escalation workflows. Excel tools that let leadership see queue status without bothering developers during code freeze. I was proud of it. Locally, I'd gotten praise. I was the youngest Operations Manager and convinced I was saving the building.

Then a VP from Seattle visited. He looked at what I'd built and said:

"This is a lot of engineering for a process that shouldn't exist. You're getting really good at the wrong thing."

He was right. I just didn't realize I'd need to learn it twice.

When your agent writes thousands of lines per day, you start looking for ways to feel useful.

PR review is perfect for this. You catch a bug. Dopamine hit. You catch another. You're contributing. You're the human in the loop. You're necessary.

I'd written before about CodeRabbit as a second reviewer. But when I analyzed 60+ addressable issues across 9 PRs, the patterns were embarrassingly predictable:

- A made up column missing from the schema

- Unvalidated environment variables at runtime

- Direct client instantiation bypassing typed factories

- Missing error boundaries in async handlers

- Implicit any in API response types

Same mistakes. Different PRs. I was playing whack-a-mole and calling it code review.

That's when I heard it again: you're getting really good at the wrong thing.

Hearing your own advice quoted back at you by your own brain is a special kind of humiliation.

So I wrote Semgrep rules—static analysis patterns that catch issues before code is even committed. Here's one:

rules:

- id: supabase-direct-create-client-import

patterns:

- pattern: import { $...IMPORTS } from "@supabase/supabase-js"

- metavariable-pattern:

metavariable: $...IMPORTS

pattern: createClient

message: "Use our typed factory: import { createClient } from '@/lib/supabase/client'"

severity: WARNINGA few minutes to write. Catches the pattern forever.

These rules now catch the patterns that made up the bulk of CodeRabbit's comments—before the code even gets committed. My PR reviews went from "here are 12 issues" to "here's 1 architectural question." That's not better code review. That's making code review unnecessary for known patterns.

No dopamine hit, though. Prevention is boring. Nobody praises you for bugs that never existed. Worth it, though.

The real work of AI development isn't managing the agent's context window. It's managing yours.

When I'm not playing human linter—catching the same non-null assertion for the twelfth time—I can actually think about the product:

- Is this the right abstraction, or just the first one that worked?

- Will users understand why this behaves the way it does?

- What happens when this fails at 2 AM and nobody's watching?

These aren't questions an AI can answer. They're not even questions a linter can ask. That's the work that compounds. You can't automate it. You can't delegate it. And you can't access it when your attention is fragmented across forty PR comments about missing try-catch blocks.

The upstream work isn't about efficiency. It's about clearing the path so your brain can do the work only your brain can do.

The measure of your code review process isn't your interception rate. It's how few patterns make it to review in the first place. Catching bugs still feels productive. That's how you know it's a trap.

Related: The Scorpion, the Frog, and the AI That Wants Your Tests to Pass